The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus"The World is beginning to know Okinawa": Ota Masahide Reflects on his Life from the Battle of Okinawa to the Struggle for Okinawa

Ota Masahide interviewed on July 20, 2010 at the Ota Peace Research Institute, Naha, Okinawa

Interview, translation, notes, and introduction by Norimatsu Satoko

Introduction

“Ota-san is the ‘Conscience of Okinawa’,” the manager of a small museum in Shuri said, when I told her I was going to interview former Governor of Okinawa Ota Masahide after leaving the museum. The museum, run by the alumni association of Okinawa Prefectural First Junior High School (now Shuri High School), commemorates their students who perished in the Battle of Okinawa. At the time of the U.S. invasion of Okinawa in late March of 1945, at least 1,787 junior high school boys across the island, mostly from age 14 to 18, were drafted by the Japanese Imperial Army as members of the “Tekketsu Kinnoutai (Blood and Iron Student Corps).” At least 921, more than half of those students, died in the Battle, the bloodiest of the Pacific War, which took over 200,000 lives, half of them local civilians.1

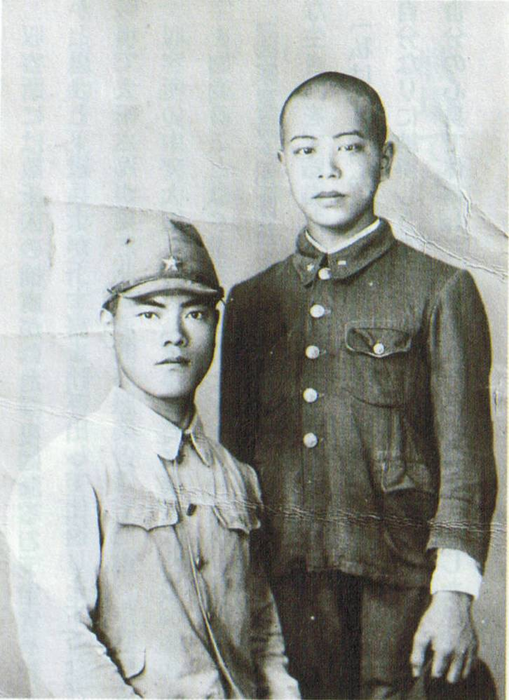

Ota Masahide (right ) as a student at Okinawa Teacher’s College

Ota, a native of Kumejima Island, about 100 kilometres west of Okinawa Island, was a 19-year old student at the Okinawa Teacher’s College when he was mobilized as a member of the communication unit of the Tekketsu Kinnoutai. Almost daily, he saw his classmates bombarded and “die the deaths not of humans, but of worms.” 226 of his 386 schoolmates died.2 He spent the last months of the Battle hiding amongst the rocks of Mabuni Beach, surviving the hunger, thirst, injury and desperation.

The rocky shore of Mabuni, the last battlefield in the desperate war, on the southern tip of Okinawa Island. Ota survived the last few months of the war hiding amongst the rocks there.

The experience of the Battle left incurable scars on Ota’s mind, as it did for many Okinawans. When the Army left its Shuri Headquarters to retreat towards the south of the island in May 1945, an injured soldier begged Ota to take him along, saying “Gakusei-san! Gakusei-san! (student, student!).” Sixty-five years later, “I still hear the soldier’s cry every day,” Ota said. “There is so much unfinished business,” as there are still thousands of bones yet to be discovered, and unexploded bombs across the island that are expected to take 40 to 50 years to dispose of. Ota ponders, “The war is far from over in Okinawa. Then why prepare for more wars?” This sentiment is shared by many Okinawans. The islanders’ strong resistance against hosting U.S. military bases is inseparable from their experience of the indescribable horrors of a war that took more than one fourth of the lives of local people. They do not just want to see another war in Okinawa; many feel responsible for indirectly participating in current U.S. wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, by providing land for their military bases, however reluctantly.

READ MORE with maps and images

![[URGENT PLEA: In Update] EMERGENCY in GANGJEONG Since AUG. 24, 2011](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiQvpaNf6EePZVucu97_JphYsFS5IgumnSiA4YAmen1PZcim6vMmW7XjZ7J6nLh-Cu36mwBN5n1evrA3ey0vYMpwlAGsgnSFggv6a1w4Qx9BvvqOB0hy0BIcBkL2Exfs3zIxBsBuDGa1kzg/s227/jejusit.jpg)

![[Solidarity from Japan for the Jeju] 253 individuals and 16 groups/organizations](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEivji7100kBkr0hzvqYfh4IBBilkZ6XgDIg89jOxS6kTssxsVKC6Wm-fZbKOEsiy3zcO-9gW6GHspD5R_2C9WsGx5S1Z5VPj_OVRF7H6dxdaT0S-2H1eqsDsYvIwOV26VscxTHnKmP5iZmh/s227/jeju_12_10j.jpg)

![[Translation] Korean organizations' statement: Immediately cancel the joint ROK-US drill Nov 26](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgfKDMo-qyEjm5asUtHlREyJY_5Ou-2tyB8SH6aUxiViRbbKR-8W_rirFiGp5DYSoD_KaeNOPMWR0af0ZPUIbJKmR89ImDvADHsGAIqsJVBvJNBEIl5wLd3G_zhPDW3Z2SxsHXadOsXe8st/s227/1.jpg)

![HOT! [Hankyoreh Hani TV] Beneath the Surface: the investigation into the sinking of the Cheonan](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEh80rL3Qv9GnfHSqbYMfivdqX5gZN-1O_VQj3A_Gk3yjWdybHwJCsprA3l6cEQB0cYCP2oNeaLo2ohLGIy0Uqqkv_fRkBevGJ2f-qkKD5eP1ZGsKeQ-r-jHUUb79WvucIN7hpEtXza4xXCL/s227/HaniTV+Cheonan.gif)

![[Translation]Statement against illegal inspection and unjust lay-off by the Kunsan USAFK!(Nov_2010)](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg3JlQ-lreusCIJo5Yv2e3ZrRwrSMUE7UQxlrDVjmBehl0Pa24QZIAbZ5vUpgnnExbkKL9PdCwxVYSHWJkr_XK0FM4EhU3CMFhqfborVNu_p4v3bEFpNm3ia-aEHnvMMuEBI27aB7_BETuJ/s227/gunsan+protest.gif)

![[Translation] Korean organizations' statement against dispatching special force to the UAE on Nov.](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiU7TNhTDLLwZkKP0Z78JsCZKp6je-QSFll3_ThmLES_y_nPLXEzeakrsZXoNxhN5blopEhy6xGV2tneJrniPdTR-JvOQMmSLr_HhlucxFvbusxk4oKvvMO2laBOHSIkB9OOeOxrQlqCA0O/s227/antiwarpeace.jpg)

![[Translation] Stop, Joining MD!: South Korean activists' statement and writing on Oct. 25, 2010](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEggGIHVei8j7LCJPJB5HIrspd942q436daNTquP-pFd45Cl70Ml_1JFiFDHgKu6FcoqNgFVKIFqjeuSPau2k_BwGHhx0cqFFL2-4ybZSTlmua0_AsERBtKYQa7jZk7uNj41LX6rj2vksHbo/s227/StopMD.jpg)

![[In Update] People First, NO G-20 (Nov. 6 to 12, Korea)](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhZl8VTqeL7o2ndliGIE-sZFCikbTgfB9KCc3AtZvDaYijBBEhdfultMEOpyrCaD5gzpH8mqfWjU20KXMbSUl-5KM7yQeHU6z3BWV8tiOy4UKaCudz9VKWoi5x58xdC_gQpJTjkR5u7O9xf/s227/left21_G20.jpg)

![[International Petition] Stop US helipad plan in Okinawa to save great nature](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEihgYmdb0N8ViPvTFC_5i-Psbt4eX_LnAUEOtZkUngv_pGvRyWag1r6W60NicLLyTgWq-sPT1hBxLY5SadEIVv5McfZQ5uIhe-W0VoflQNqojsYZjFW6AH-gB1jsmSDGnGuKIFk2UkvNbFG/s227/yanbaru_w.jpg)

![[Global Network] against the first launch of Quasi-Zenith Satellite, Japan, on Sept. 11, 2010](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEj2sYpfodDDMIA7qXwuda0DmKapxXFB479fDnn8RKy7QNZqz0VEvWucNd-DleZ37hWNXC-Z8QtaqtM37VuPwac5SgclJ9_khBBSWOedvm19MRXIP1j1kcWrK6EW5IFjQdEEY2h7E6xuyNvC/s227/Qzss-45-0_09.jpg)

![[In update] Some collections on the Koreans’ protests against the sanction & war on Iran](http://4.bp.blogspot.com/_gnM5QlRx-4c/TJMvke6t8zI/AAAAAAAAFO4/tamQ8LUnOOA/S227/No+Sanction+on+Iran.jpg)

![[Three International Petitions] to End the Korean war and peace treaty(or peace resolution)](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhlohLVYtpCg7iMsZhNYY4hBbhTi2dIheHMHWLDph9X2y78cjgZV1LeSfUJeu80elhJm70Q9E059q72lK-spSPvsRG4bPuCDIytltJB9IH3mWt9OG98HqhnTsPakwhvNeoCFUgF1xoxQ2EZ/s227/border.jpg)

![[Collection of Documents] No Base Learning and Solidarity Program_Korea(June 14 to 20, 2010)](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEix_HzjToh3nNGHBc-_5gasq-ykcaZ6GInLixILmZVyRJ5xoeHCxWOyYd9fSM7bmnuFsjSrYOGEPnQOwB1Dcyo-sN4Pw0cFPhUtKig_qlVnGL1Wi82ClvPqbEPWYhJiqdNF0DyzLIBETMB9/s227/No-Base-banner.jpg)

![Site Fwd:[John Hines] A U.S. Debate coach’s research trip on the Issues of Korea](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg8yRra0zNhKHN74Auqhd3Nx9tZ7BWCGflRJHGH4CfzBT_yjhZ8Nl9b3OZuLpYWJ2exsjmR0oVl-Qq_cf832p2VdmOZhUi-lCFzCNeDSyVtweX1lWZPC-RlHmDMLtilHwHjNFTenBiM4Fk4/s227/Jeju-Peace-Tour.jpg)

![[News Update] Struggle Against the Jeju Naval Base since Jan. 18, 2010](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhKfSTRC5QKBBSFIq_m7QIqXdlbL4-gF5GJYn9Q-pN__k7sV7uxGDcLY5L8xmU7QuWuUhBT_GhG-URBPO80RT3AfWfDrWJr06h1hFuZC6ZBVKe4U6PS1Cd7Kr6olO8TYQtk13Drox7IS6ea/s226/scrum1.jpg)

![[Urgent] Please spread the Letter!: There was no Explosion! There was no Torpedo! (May 26, 2010)](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhSd2yWZ3xGwnJQXB73z5FgXCqSosAoB9_33-GLYprOmLqjmvgSAQp1BYI7e4slK1FDxHRi9KK4um-OpDaj8QOkXwAScVAgvvq6-ehbDA-hbkr96wT9oHNNmWnBPv8GU4hoZp9X8F9AZBX4/s227/grounded.jpg)

![Text Fwd: [Stephen Gowans]The sinking of the Cheonan: Another Gulf of Tonkin incident](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEi_L6hB3RZ1MovTXHe0A8yn_RfgMALGR0kM6poBuGp809xwvHtB_-PGWtS_WpyPWatyd9lB2pPqL2gOLc4dTCEdJ9sMvxJWEdapl-mMLm7WHAsV-jVpgqarVh8XBtdz_0c-Vohdh3HtJahD/s227/lee-myung-bak.jpg)

![[Japan Focus]Politics in Command: The "International" Investigation into the Sinking of the Cheonan](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiHmTo8v-uCJnabRhMdnBAkC9J3s5bb2JsDKiT5leJHwbK8IDJHxfJmqQ_C0Is_bPC6UGMf05CA0exF2y4r2x9RhFUHT0kjsKviaME_MZXKnq775UyYAdb7w2SAzE75XvBfHp1al2q6i3cf/s227/wen_jiabao_and_lee_myungbak.png)

![[Japan Focus] Who Sank the SK Warship Cheonan? A New Stage in the US-Korean War and US-China](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiKSS5ULT5QBaMGYpXXqBMX9jtwLwMLuK469b6Ku72GTJYKUObzTANaPjZqvvpPzYMJgPF53sjhvhK3DVa88ipYlggsJageykXlkxY6s8TW05xcU-_vfhf-pACUoaWuFbT-fsU1qEhm_yIi/s227/buoy_map.gif)

![[Updated on 12/13/10] [Translation Project] Overseas Proofs on the Damages by the Military Bases](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEikADE6JovUNspQyZUWVMTLAQg7yQNqXpVUbqZPk8f4uc_1723_xm1Cco6WAmstQXVPnaJAcb1mZA8Ny_3xONT_f5uh8MNLPnUhtqdGgy3HCtC1Vbbz4Q0ZY1Cssu-4cJEVNdrvznbS5UzO/s227/missile.jpg)

![[International Petition] Close the Bases in Okinawa](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhNpQiHklwFbWVlFK7GDFXnBSOOSFEj3Il-We-N3uTDldKiidL2NGZs7X_LtTnatzTo_r8CexRkFe8NhfxYqmgp1knEEslROTfNjI5_mSb57cdbhPkftvanveYBaevAD9xuKDGoIxiTwoSb/s227/2.jpg)

![[In Update]Blog Collection: No Korean Troops in Afghanistan](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjjEmCRXSNAG7_QBxKWbdksmxoWR4nyAovQTTdR1G2AuXh0jxtqNkI9OmYgYWRoLAJShvtBvE840QXuBWSVh3u3zMYqkNAFX6OWy3m5Nur4HM7uNK-pKT1ycyApJp-VLyhIFRRcoisYAh0E/s226/No-Troops-to--Afghanistan.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment