Stop NATO

August 9, 2009

Afghan War: NATO Builds History's First Global Army

Rick Rozoff

Two months before the eighth anniversary of the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan and the beginning of NATO's first-ever ground war the world is witness to a 21st Century armed conflict without end waged by the largest military coalition in history.

With recent announcements that troops from such diverse nations as Colombia, Mongolia, Armenia, Japan, South Korea, Ukraine and Montenegro are to or may join those of some 45 other countries serving under the command of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization-led International Security Assistance Force (ISAF), there will soon be military personnel from fifty nations on five continents and in the Middle East serving under a unified command structure.

Never before have soldiers from so many states served in the same war theater, much less the same country.

By way of comparison, there were twenty six (higher, and looser, estimates go as high as 34) national contingents in the so-called coalition of the willing in Iraq as of 2006. In the interim between now and then troops from all contributing nations but the United States and Great Britain have been withdrawn and in most cases redeployed to Afghanistan.

In 1999 NATO's fiftieth anniversary summit in Washington, D.C. welcomed the first expansion of the world's only military bloc in the post-Cold War era, absorbing former Warsaw Pact members the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland, in the course of conducting NATO's first war, the relentless 78-day bombardment of Yugoslavia, Operation Allied Force.

Two years later, after the 9/11 attacks in New York City and Washington, D.C., NATO activated its Article 5 - "The Parties agree that an armed attack against one or more of them in Europe or North America shall be considered an attack against them all" - for the first time in the bloc's history and launched a number of operations from deploying German AWACS to patrol the Atlantic Coast of the U.S. to launching Operation Active Endeavor, a naval surveillance and interdiction program throughout the Mediterranean Sea which continues to this day.

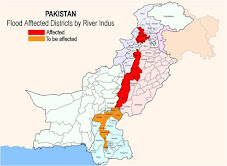

But the main effect, and the main purpose, of invoking NATO's mutual military assistance clause was to rally the then 19 member military bloc for the invasion and occupation of Afghanistan and the stationing of troops, warplanes and bases throughout South and Central Asia, including in Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. Flyover rights were also arranged with Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan and newly acquired airbases in Bulgaria and Romania have since been used for the transit of troops and weapons to the Afghan war zone.

If the 1999 war against Yugoslavia was NATO's first "out of area" operation - that is, outside of North America and those parts of Europe in the Alliance - the war in Afghanistan marked NATO's transformation into a global warfighting machine. In the years intervening between the October 2001 invasion of Afghanistan and now NATO officials and advocates have come to employ such terms as Global, Expeditionary and 21st Century NATO. Afghanistan provided the Alliance the opportunity to add to its previous expansion to Eastern Europe with its attendant military operations in the Balkans into asserting itself as the world's first global military force.

As the U.S. State Department's Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for European Affairs Kurt Volker (later U.S. ambassador to NATO) said in 2006, “In 1994 NATO was an alliance of 16 [countries], without partners, having never conducted a military operation. By 2005, NATO had become an alliance of 26, engaged in eight simultaneous operations on four continents with the help of 20 partners in Eurasia, seven in the Mediterranean, four in the Persian Gulf, and a handful of capable contributors on our periphery.” [1]

The updated details of what he was alluding to are these:

From 1999 to this year NATO has added twelve new members - Albania, Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia - all in Eastern Europe, nine of them formerly in the Warsaw Pact and three former Soviet and two Yugoslav republics.

All of the new members were prepared for full NATO accession under the Partnership for Peace (PfP) program, which first demands weapons interoperability (scrapping contemporary Russian and old Warsaw Pact arms in favor of Western ones), increasing future members' military spending to 2% of the national budget no matter how hard-hit the nation is since the collapse of the Eastern Bloc, the purging of "politically unreliable" personnel from military, defense and security posts, training abroad in NATO military academies, hosting U.S. Alliance military exercises, and instructing the officer corps in a common language - English - for joint overseas operations.

With a dozen PfP graduates now full NATO members who have deployed troops to Afghanistan - Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland and Romania were also levied for troops in Iraq - the partnership still includes every former Soviet Republic not already in NATO but Russia - Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine and Uzbekistan - and ten European nations that had never before been part of a military bloc: Austria, Bosnia, Finland, the Republic of Ireland, Macedonia, Malta, Montenegro, Serbia, Sweden and Switzerland.

All of the latter but Malta and Serbia have been tapped for soldiers in Afghanistan. The 28 full NATO members all have troops there also.

Of the former Soviet republics, troops from Armenia, Azerbaijan, Estonia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Latvia, Lithuania, Moldova and Ukraine served in Iraq under PfP obligations. At the time of the South Caucasus war last August Georgia had the third largest national contingent in Iraq - 2,000 troops deployed near the Iranian border - which the U.S. rushed home on transport planes for the war with Russia.

NATO also upgraded its Mediterranean Dialogue, whose partners are Algeria, Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Mauritania, Morocco and Tunisia, at the 2004 NATO summit in Istanbul, Turkey with the so-called Istanbul Cooperation Initiative, which also laid the groundwork for military integration of the six members of the Gulf Cooperation Council: Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. The last-named is the only Arab state to date with troops in Afghanistan.

The Afghan war has led to another category of NATO partnership, that of Contact Countries, which so far officially include Australia, Japan, New Zealand and South Korea.

The Alliance also has a Tripartite Commission with Afghanistan and Pakistan for the prosecution of the dangerously expanding war in South Asia, and defense, military and political leaders from both nations are regularly summoned to NATO Headquarters in Belgium for meetings and directives.

Afghan and Pakistani soldiers are trained at NATO bases in Europe.

Though not members of formal partnerships, nations with troops serving under NATO in Afghanistan like Singapore and Mongolia have been pulled into the bloc's global nexus and necessarily adopt military doctrines and structures in line with NATO standards.

Another component of the 2001 decision to activate the Alliance's Article 5 provision was to deploy NATO forces to the Horn of Africa, primarily to Camp Lemonier in Djibouti, where they have conducted maritime surveillance and boarding operations ever since. Last autumn NATO deployed its first naval task force off the coast of Somalia.

In addition to the five African nations in the Mediterranean Dialogue, NATO has expanded its penetration of the continent over the past eight years: An Alliance naval group has docked in Kenya. NATO has held military maneuvers in South Africa. Even Libya has begun cooperation with NATO in the Mediterranean.

With the launching of the Pentagon's Africa Command (AFRICOM) last year - and AFRICOM is the personal project of retired Marine General James Jones, from 2003-2006 top military commander of NATO and the U.S. European Command where AFRICOM was incubated and now U.S. National Security Adviser - the distinction between Pentagon and NATO operations in Africa will be a largely academic one and all of Africa's 53 nations except for Eritrea, Sudan and Zimbabwe are potential Alliance partners.

The central focus for the operationalization of NATO's worldwide plans is Afghanistan and adjoining nations.

In calendar year nine of the war in that nation and now with its expansion into Pakistan NATO has built upon previous and current joint military deployments in Bosnia, Albania, Kosovo, Macedonia, Djibouti, Iraq, Kuwait, Jordan, Sudan and off the coast of Somalia and secured a long-term, indeed a permanent, laboratory for molding history's first international rapid deployment, combat and occupation military force; a 650,000 square kilometer firing and weapons testing range; a string of airbases in the center of where Russian, Chinese, Indian and Iranian regional interests converge; a boot camp for breaking in the armed forces of dozens of nations slated for NATO membership.

As such, discussions about the "winnability" of the current war are beside the point.

Although there are currently over 100,000 troops serving under U.S. and NATO command in Afghanistan, many of them so-called niche deployment special forces, mountain and airborne troops and other units ordered by NATO from member and candidate nations, on August 7 the newly-installed Alliance Secretary General Anders Fogh Rasmussen issued an "open call for more troops" which "was perhaps the clearest indication yet that a major escalation ordered this year by new U.S. President Barack Obama is far from over."

In Rasmussen's words, "Honestly speaking, I think we need more troops." [2]

Two days after being sworn in as NATO chief on August 1 Rasmussen "ruled out setting a deadline for the withdrawal of international forces from Afghanistan, saying the western alliance will stay there 'for as long as it takes.'" [3]

The new secretary general hadn't time to begin to settle into his new post when he and NATO Supreme Allied Commander James Stavridis flew into Kabul on an unscheduled visit two days afterwards "in order to get a comprehensive view of the international effort." [4]

On August 7 British General David Richards, who will become Chief of the General Staff on August 28, stated that "There is absolutely no chance of Nato pulling out" [5] of Afghanistan and that his own nation's role there "might take as long as 30 to 40 years." [6]

Eight days earlier the British ambassador to the U.S., Sir Nigel Sheinwald, anticipated Richards in saying of the British - and by implication NATO - role in South and Central Asia that "This is going to be for decades...." [7]

In late July the Afghan ambassador to the U.S. also revealed that any hopes for an imminent deescalation of the war in his country, not to mention its eventual end, were non-existent by revealing that "NATO countries will provide 8,000 to 10,000 additional troops to allow Afghans to vote securely" [8] in this month's national elections. The official explanation by the U.S. and NATO for their increased deployment of troops to Afghanistan is that it is an ad hoc effort to insure the elections there proceed without interruption, but past elections have occurred and the fighting has increased with the introduction of more and yet more Western soldiers, tanks and other armor, attack helicopters, warplanes and large-scale military offensives.

In fact August is a good month for a NATO summer offensive and concerns over elections are a public relations ploy.

Further reading

Monday, August 10, 2009

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

![[URGENT PLEA: In Update] EMERGENCY in GANGJEONG Since AUG. 24, 2011](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiQvpaNf6EePZVucu97_JphYsFS5IgumnSiA4YAmen1PZcim6vMmW7XjZ7J6nLh-Cu36mwBN5n1evrA3ey0vYMpwlAGsgnSFggv6a1w4Qx9BvvqOB0hy0BIcBkL2Exfs3zIxBsBuDGa1kzg/s227/jejusit.jpg)

![[Solidarity from Japan for the Jeju] 253 individuals and 16 groups/organizations](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEivji7100kBkr0hzvqYfh4IBBilkZ6XgDIg89jOxS6kTssxsVKC6Wm-fZbKOEsiy3zcO-9gW6GHspD5R_2C9WsGx5S1Z5VPj_OVRF7H6dxdaT0S-2H1eqsDsYvIwOV26VscxTHnKmP5iZmh/s227/jeju_12_10j.jpg)

![[Translation] Korean organizations' statement: Immediately cancel the joint ROK-US drill Nov 26](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgfKDMo-qyEjm5asUtHlREyJY_5Ou-2tyB8SH6aUxiViRbbKR-8W_rirFiGp5DYSoD_KaeNOPMWR0af0ZPUIbJKmR89ImDvADHsGAIqsJVBvJNBEIl5wLd3G_zhPDW3Z2SxsHXadOsXe8st/s227/1.jpg)

![HOT! [Hankyoreh Hani TV] Beneath the Surface: the investigation into the sinking of the Cheonan](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEh80rL3Qv9GnfHSqbYMfivdqX5gZN-1O_VQj3A_Gk3yjWdybHwJCsprA3l6cEQB0cYCP2oNeaLo2ohLGIy0Uqqkv_fRkBevGJ2f-qkKD5eP1ZGsKeQ-r-jHUUb79WvucIN7hpEtXza4xXCL/s227/HaniTV+Cheonan.gif)

![[Translation]Statement against illegal inspection and unjust lay-off by the Kunsan USAFK!(Nov_2010)](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg3JlQ-lreusCIJo5Yv2e3ZrRwrSMUE7UQxlrDVjmBehl0Pa24QZIAbZ5vUpgnnExbkKL9PdCwxVYSHWJkr_XK0FM4EhU3CMFhqfborVNu_p4v3bEFpNm3ia-aEHnvMMuEBI27aB7_BETuJ/s227/gunsan+protest.gif)

![[Translation] Korean organizations' statement against dispatching special force to the UAE on Nov.](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiU7TNhTDLLwZkKP0Z78JsCZKp6je-QSFll3_ThmLES_y_nPLXEzeakrsZXoNxhN5blopEhy6xGV2tneJrniPdTR-JvOQMmSLr_HhlucxFvbusxk4oKvvMO2laBOHSIkB9OOeOxrQlqCA0O/s227/antiwarpeace.jpg)

![[Translation] Stop, Joining MD!: South Korean activists' statement and writing on Oct. 25, 2010](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEggGIHVei8j7LCJPJB5HIrspd942q436daNTquP-pFd45Cl70Ml_1JFiFDHgKu6FcoqNgFVKIFqjeuSPau2k_BwGHhx0cqFFL2-4ybZSTlmua0_AsERBtKYQa7jZk7uNj41LX6rj2vksHbo/s227/StopMD.jpg)

![[In Update] People First, NO G-20 (Nov. 6 to 12, Korea)](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhZl8VTqeL7o2ndliGIE-sZFCikbTgfB9KCc3AtZvDaYijBBEhdfultMEOpyrCaD5gzpH8mqfWjU20KXMbSUl-5KM7yQeHU6z3BWV8tiOy4UKaCudz9VKWoi5x58xdC_gQpJTjkR5u7O9xf/s227/left21_G20.jpg)

![[International Petition] Stop US helipad plan in Okinawa to save great nature](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEihgYmdb0N8ViPvTFC_5i-Psbt4eX_LnAUEOtZkUngv_pGvRyWag1r6W60NicLLyTgWq-sPT1hBxLY5SadEIVv5McfZQ5uIhe-W0VoflQNqojsYZjFW6AH-gB1jsmSDGnGuKIFk2UkvNbFG/s227/yanbaru_w.jpg)

![[Global Network] against the first launch of Quasi-Zenith Satellite, Japan, on Sept. 11, 2010](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEj2sYpfodDDMIA7qXwuda0DmKapxXFB479fDnn8RKy7QNZqz0VEvWucNd-DleZ37hWNXC-Z8QtaqtM37VuPwac5SgclJ9_khBBSWOedvm19MRXIP1j1kcWrK6EW5IFjQdEEY2h7E6xuyNvC/s227/Qzss-45-0_09.jpg)

![[In update] Some collections on the Koreans’ protests against the sanction & war on Iran](http://4.bp.blogspot.com/_gnM5QlRx-4c/TJMvke6t8zI/AAAAAAAAFO4/tamQ8LUnOOA/S227/No+Sanction+on+Iran.jpg)

![[Three International Petitions] to End the Korean war and peace treaty(or peace resolution)](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhlohLVYtpCg7iMsZhNYY4hBbhTi2dIheHMHWLDph9X2y78cjgZV1LeSfUJeu80elhJm70Q9E059q72lK-spSPvsRG4bPuCDIytltJB9IH3mWt9OG98HqhnTsPakwhvNeoCFUgF1xoxQ2EZ/s227/border.jpg)

![[Collection of Documents] No Base Learning and Solidarity Program_Korea(June 14 to 20, 2010)](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEix_HzjToh3nNGHBc-_5gasq-ykcaZ6GInLixILmZVyRJ5xoeHCxWOyYd9fSM7bmnuFsjSrYOGEPnQOwB1Dcyo-sN4Pw0cFPhUtKig_qlVnGL1Wi82ClvPqbEPWYhJiqdNF0DyzLIBETMB9/s227/No-Base-banner.jpg)

![Site Fwd:[John Hines] A U.S. Debate coach’s research trip on the Issues of Korea](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg8yRra0zNhKHN74Auqhd3Nx9tZ7BWCGflRJHGH4CfzBT_yjhZ8Nl9b3OZuLpYWJ2exsjmR0oVl-Qq_cf832p2VdmOZhUi-lCFzCNeDSyVtweX1lWZPC-RlHmDMLtilHwHjNFTenBiM4Fk4/s227/Jeju-Peace-Tour.jpg)

![[News Update] Struggle Against the Jeju Naval Base since Jan. 18, 2010](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhKfSTRC5QKBBSFIq_m7QIqXdlbL4-gF5GJYn9Q-pN__k7sV7uxGDcLY5L8xmU7QuWuUhBT_GhG-URBPO80RT3AfWfDrWJr06h1hFuZC6ZBVKe4U6PS1Cd7Kr6olO8TYQtk13Drox7IS6ea/s226/scrum1.jpg)

![[Urgent] Please spread the Letter!: There was no Explosion! There was no Torpedo! (May 26, 2010)](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhSd2yWZ3xGwnJQXB73z5FgXCqSosAoB9_33-GLYprOmLqjmvgSAQp1BYI7e4slK1FDxHRi9KK4um-OpDaj8QOkXwAScVAgvvq6-ehbDA-hbkr96wT9oHNNmWnBPv8GU4hoZp9X8F9AZBX4/s227/grounded.jpg)

![Text Fwd: [Stephen Gowans]The sinking of the Cheonan: Another Gulf of Tonkin incident](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEi_L6hB3RZ1MovTXHe0A8yn_RfgMALGR0kM6poBuGp809xwvHtB_-PGWtS_WpyPWatyd9lB2pPqL2gOLc4dTCEdJ9sMvxJWEdapl-mMLm7WHAsV-jVpgqarVh8XBtdz_0c-Vohdh3HtJahD/s227/lee-myung-bak.jpg)

![[Japan Focus]Politics in Command: The "International" Investigation into the Sinking of the Cheonan](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiHmTo8v-uCJnabRhMdnBAkC9J3s5bb2JsDKiT5leJHwbK8IDJHxfJmqQ_C0Is_bPC6UGMf05CA0exF2y4r2x9RhFUHT0kjsKviaME_MZXKnq775UyYAdb7w2SAzE75XvBfHp1al2q6i3cf/s227/wen_jiabao_and_lee_myungbak.png)

![[Japan Focus] Who Sank the SK Warship Cheonan? A New Stage in the US-Korean War and US-China](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiKSS5ULT5QBaMGYpXXqBMX9jtwLwMLuK469b6Ku72GTJYKUObzTANaPjZqvvpPzYMJgPF53sjhvhK3DVa88ipYlggsJageykXlkxY6s8TW05xcU-_vfhf-pACUoaWuFbT-fsU1qEhm_yIi/s227/buoy_map.gif)

![[Updated on 12/13/10] [Translation Project] Overseas Proofs on the Damages by the Military Bases](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEikADE6JovUNspQyZUWVMTLAQg7yQNqXpVUbqZPk8f4uc_1723_xm1Cco6WAmstQXVPnaJAcb1mZA8Ny_3xONT_f5uh8MNLPnUhtqdGgy3HCtC1Vbbz4Q0ZY1Cssu-4cJEVNdrvznbS5UzO/s227/missile.jpg)

![[International Petition] Close the Bases in Okinawa](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhNpQiHklwFbWVlFK7GDFXnBSOOSFEj3Il-We-N3uTDldKiidL2NGZs7X_LtTnatzTo_r8CexRkFe8NhfxYqmgp1knEEslROTfNjI5_mSb57cdbhPkftvanveYBaevAD9xuKDGoIxiTwoSb/s227/2.jpg)

![[In Update]Blog Collection: No Korean Troops in Afghanistan](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjjEmCRXSNAG7_QBxKWbdksmxoWR4nyAovQTTdR1G2AuXh0jxtqNkI9OmYgYWRoLAJShvtBvE840QXuBWSVh3u3zMYqkNAFX6OWy3m5Nur4HM7uNK-pKT1ycyApJp-VLyhIFRRcoisYAh0E/s226/No-Troops-to--Afghanistan.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment